PECULIARITIES THE CHELOK HAVE FOUND IN THEIR CAPITAL, DHEGHО̄M

By Jaqehura Fadasa (a.k.a. Verdant Hilltop)

Former Archaeologist, Voliloshoku Academy of Xenoarchaeology (defunct)

Note: Time and space units translated to common measures

"If I knew when the world began, I've would have started my account from there..." — Common saying among chelok historians

It’s funny; after all these years, the thrill of the dig has never left me. The field still calls, and my students manage the stacks of paperwork while I descend into ancient chelok sites, some buried nearly a hundred feet below. These structures once served myriad purposes across centuries, and each level we excavate reveals some new layer of their ingenuity. I’ve studied the chelok's history in the safe predictability of academia for decades, but nothing—no lecture, no account—prepared me for standing on Dheghо̄m's soil.

My fascination with the chelok's vibrant past brought me here. The decision wasn’t easy, but when I heard rumors that ship scrappers were gathering for an expedition to the defunct Hoku Expansion sites, I knew it was time to take a break from our academy and dive headlong into this journey. My team needed little convincing, and soon we found ourselves on board, headed toward a culture that still surprises me at every turn.

THE TRIP

Unlike most of my peers, I belong to one of the last generations that remembers the Expanse in its golden age, before the Relentless Force arrived. My training as an archaeologist might seem impractical for a people facing extinction, but it proves invaluable to these so-called “pirates” who rely on me to interpret and locate high-value tech from the Expanse. Our ways of building and defending were utterly foreign to them.

We left Forzai, charting a course straight to the heart of the Expanse. Our arrene sponsors granted us the rare privilege of manning a mining vessel, the Eye of Ririth—a name borrowed, they told us, from an ancient arrene hero of the forge. In return, they expected us to return with riches enough to justify the costs. While the established starlanes might have cut our journey down to nine months, our frequent stops stretched it into a grueling two-year trek to reach Hoku space.

For most of the scientific crew, however, the journey itself was familiar territory. We were accustomed to long stretches in icy outposts and desolate bases, and months of open space travel hardly fazed us. The fall of the Expanse has brought hoku from diverse backgrounds closer together; after all, we’re all orphans of a civilization that once spanned dozens of systems. Salvaging what remains of our shared history and cultural exchanges feels like the right thing to do, a last attempt to preserve what little we have left. The arrene and qire crews, meanwhile, kept to themselves in their own sections of the ship, emerging only at major stops for refueling or trade deep within the starlanes. They were little more than distant figures, barely heard or seen outside these stops.

Inside the Expanse, our true adventure began. We halted by several derelict mining systems rumored to have been used by pre-war militias for repairs and operations. We hoped these forgotten systems would reveal caches of hoku warships, old but salvageable, some still outfitted with the powerful weaponry they were famed for. As the only natives on board, my team was tasked with identifying and cataloging any equipment we found and disabling genetic locks on military installations. To our surprise, we discovered hangars filled with hoku starfighters. Some sat unfinished; others had awaited pilots who would never return. These vessels carry immense cultural significance for my people, but our requests to preserve a few went unanswered by the crew. It didn't cost us much to try and ask anyway.

In the end, we brought back a dozen starfighters—half of which were still operational. I was ordered by the captain to oversee the scrapping of another two dozen fighters, their jump-drives and weapons carefully extracted and stored. The process was tense and painstaking; a single misstep could have set off a chain reaction in the asteroid belt, lighting it up like a string of holiday fireworks.

[missing image]

Our mission wasn’t just about salvaging war machines; the other half of our cargo was to include as many chelok artifacts as we could unearth. The Hoku Expanse, being close to the ancient world of Dhegо̄m, was a prime spot for scavenging old tech, particularly for those willing to smuggle it. Our arrene sponsors were eager for anything functional, or even slightly salvageable, that could fetch a high price. Thanks to old literature and stories from home, I knew of several places where these pirates might just find their treasure—one of which was back on my homeworld, Voliloshoku.

Many capital worlds in the Expanse were left in eerie stasis after the Unrelenting Force’s “cleansing”—in some cases, entire cities were simply glassed over. Afterward, the Force withdrew, leaving them as strange ghost worlds. Despite this apparent retreat, caution was essential; the heart of the Expanse, especially around the Muhori and Paza systems, is rumored to still see periodic patrols. If any encounter were to happen, well—there’d be little one could do.

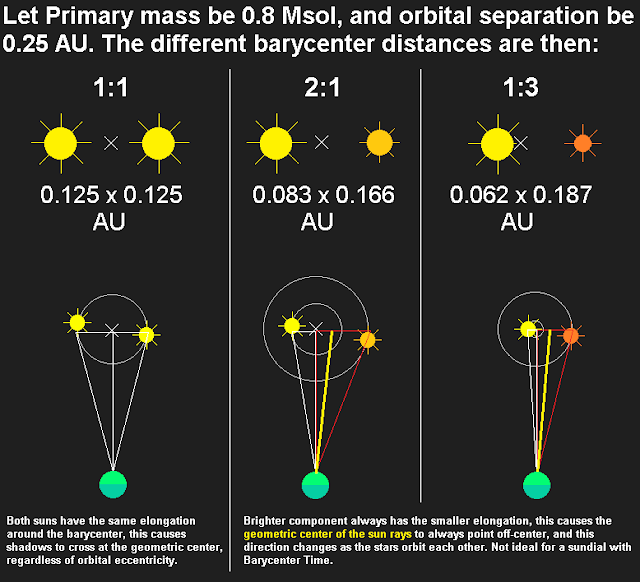

Voliloshoku is an odd, perhaps one-of-a-kind world, orbiting a red dwarf star at the Lagrange point of its companion, a larger and much brighter white star. As a result, its climate is capricious, cycling between freezing at nightfall and nearly boiling by midday, with temperatures swinging week by week as we near and retreat from its two primary suns. Despite its striking brightness and its three stars, Voliloshoku is no paradise; it’s more of a swampy, wet expanse with dense, heavy air. Few animals survive, and the glassing of major colonies wiped out nearly all vegetation. Shielding is a must to survive the daylight heat.

Yet for all its inhospitable conditions, Voliloshoku has always enticed explorers, and we Hoku weren’t the first to ask if its unforgiving environment could be conquered. Ruins lie beneath the dense swamps at the southern pole, structures attributed to early chelok settlers from some seven thousand years ago. The site speaks of a grand civilization, but it was abandoned—most likely due to extreme radioactivity blanketing the region. No one’s certain whether the radioactive contamination resulted from a massive nuclear waste leak or an ancient war-time bombardment, but what remains is a field of oxidized chelok relics buried in the mud, along with similarly haunting relics on other planets orbiting the red dwarf, Nigutal’za. These sites held little interest for the crew, though. After a few days, they found no “marketable” treasure among the weathered ruins and left nonchalantly.

I felt a pang of frustration at leaving these ruins behind, yet the crew was more than pleased to discover an intact, dormant communications satellite. Re-purposing it meant we could boost the Eye of Ririth’s radar capacity, a considerable upgrade. One of my technicians assisted the crew in transferring and installing its components in the following three weeks.

[missing image]

The icy poles of Nigutaline—the planet closest to Nigutal’za—were our next stop, a convenient location to replenish our water and helium supplies. But they also held a hidden surprise: another dormant hangar, half-buried beneath the ice. From the looks of it, we weren’t the first ones here. The signs of previous visitors—abandoned hacking tools and drilling equipment, presumably left by other pirates—suggested they’d tried breaking through the base walls. Yet it appeared they hadn’t managed to get very far. Thanks to my native credentials, we were able to access the purifying station, which, remarkably, was still largely operational.

With some convincing, I got the crew to agree to bring along a native Volkalian cargo ship we’d discovered in the hangar. I argued that the extra range it provided would uncover far more valuable finds—more than enough to cover the debt for towing it along with us. This proved to be a turning point, as the cargo ship happened to carry exosuits suitable for our kind, a sorely needed resource on this hostile planet. Until then, we had been using barely-compatible exosuits, which was hardly ideal for serious exploration.

At this point, we still faced another three months of starlane travel before reaching Dheghо̄m. With no further obstacles in our way, we prepared to settle into the final stretch, though our arrival would be delayed by a few days thanks to some damage to our lightsail.

During this leg of the journey, we crossed paths with a returning Qire merchant ship. The encounter proved profitable, as we managed to offload two of the unmarked Hoku starfighters we’d salvaged. It was a rare chance to trade in a secluded region, and the Qire’s interest in the starships was a small but welcome boost to our mission funds.

ARRIVAL AT DHEGHО̄M

Since Hoku port licenses are no longer recognized by the Dominion or Chelok space, we needed to re-register the ship under standard naval law, which delayed our touchdown by about four days. As part of the re-registration, we had to choose a new name for the ship. After some debate, we settled on Kotishera, after the ancient Hukat goddess of Crafts and War. The new registry—MOV 201 KTXR—felt like a fresh beginning to our expedition.

[missing image]

Dhegо̄m, in comparison to the grandiose but now-defunct Hoku capital of Hokushoku, is a relatively small oceanic planet graced by two moderately-sized moons. We had a spectacular view of these moons throughout our descent—a view that remained unbroken, as our newly named Kotishera lacks direct landing capabilities. To reach the surface, we had to charter a small freighter from lunnocentric orbit (their term for our position above Dhegо̄m), which came at a notably steep price.

The descent included a stop at Dhegо̄m’s stationary port station, where we underwent meticulous entry protocols: comprehensive checks, full-body scans, and, most noticeably, an intense sterilization process that left our suits and skin bleached and suntanned. Finally, after the endless procedures, we boarded a modest but surprisingly comfortable shuttle for the hour-long flight down to Urafar—their port capital. The city reminded me of Aa-Iritesh’akar back on Argost, blending the familiar rhythms of a bustling harbor with the singular cultural quirks of the Chelok.

Urafar sprawls across the base of an immense canyon, its concentric ring-like districts carved directly into the canyon floor. Towering walls rise hundreds of meters above, enclosing the city in a natural fortress, where the only exits lead either downstream along the river or up through dozens of imposing gates embedded in the rock. Surrounding the canyon, a temperate forest cascades downwards, appearing to spill into the city like a verdant waterfall. Within the canyon, the climate is markedly different from the outer landscape: the higher atmospheric pressure here traps humidity and warmth, nurturing a stretch of dense rainforest that pushes inward from the north, creating a microcosmic jungle at odds with the land above.

The city’s architecture feels like a relic of ancient grandeur, with monumental stone-carved pyramids, wide stone roadways, and imposing monuments that give the city an almost timeless quality. Urafar’s commercial centers are the only nod to contemporary styles, utilizing reinforced steel and glass, yet even these structures echo the classical forms that define Chelok aesthetics. Between each district, green reserves and vast farms occupy the spaces, a sustainable and serene arrangement. Ingenious irrigation systems divert water from the upstream river to feed these green belts, channeling it through circular purification pools before returning it to the delta below. This canyon, a product of billions of years of continental shifts, will eventually open into a strait—a slow yet relentless reminder of time’s passage, as is the city itself.

[missing image]

As we navigated Urafar, it became clear that parts of the city were undergoing active restoration. Freshly cut stones and the diligent work of masons were visible in various pockets of the canyon city, where they seemed focused on preserving the ancient look of stairways, roads, and building facades. This meticulous restoration process was balanced by restrictions on heavy vehicles, which are only allowed in designated lanes and zones to prevent wear on these historic structures. As a result, everyone is encouraged to walk or use bicycles, which adds to the city’s distinctive atmosphere and pace.

Our guide led us to an "ancient" hotel reputedly in operation for thousands of years. The building had the gravitas and old-world charm befitting such claims, but we couldn't help feeling some skepticism about the extent of its antiquity. It seemed almost too perfectly curated for foreign visitors, down to the intricate designs supposedly "unmodified" for millennia. Still, the city’s authenticity and beauty were undeniable, even if, as in any proper city, a few opportunistic locals saw an easy chance to embellish their stories for a higher price.

APPEARANCE

At this point, my team and I had grown fairly accustomed to the physionomy of the chelok, along with a grasp of their customs. Still, I realize my peers reading these records may not be familiar with this species, especially considering that most of us have kept to preservation colonies since the Fall. I'll do my best to describe their appearance and behaviors, as they stand apart from other species within the Dominion.

The Chelok are a species that stands in stark contrast to the shorter beings often found in the Dominion. While other species rarely surpass 1.6 meters in height, the Chelok are notably taller, with even their shortest members matching our height—standing eye-to-eye with a Hoku. Their posture is upright, walking on two legs like us, which sets them apart from species like the Arrene, who are strong but more hunched, with short ankles that limit their ability to stand tall, or the nagiv which walk on multiple appendages.

In terms of physique, the Chelok are quite similar to Hoku, though there are noticeable differences in their anatomy. Their feet are broad and flat, supporting their upright stance, with small, forward-facing toes. Each hand has five fingers, including a robust thumb that rests inward when at rest, giving their hands a unique, almost grasping form, distinct from our own. This configuration makes their hands both versatile and precise, the vague resemblance between chelok and hoku hand form both relate to a common adaptation for living on a forest's canopy, brachiation as it is called. Though for some reason, the chelok have long descended from the trees to the plains of their world far earlier than us hoku, thus, our stronger grip shape compared to theirs.

It’s fascinating to consider how the Chelok, despite developing nearly in parallel with us Hoku, have maintained a lead in advancement for at least twenty to thirty thousand years. The shape of their evolution, while similar to ours in some respects, diverged in subtle but crucial ways that allowed them to forge a different path—and perhaps an easier one in their world of shifting plains and temperamental seasons. For them, leaving the canopy behind was a matter of necessity rather than choice, but that necessity proved to be an advantage. Their hands, versatile but unspecialized, adapted quickly to the complex demands of tool-making, a skill that was already well-developed among them by the time our ancestors were still swinging between the trees of Hokushoku.

Our own evolutionary path was stable, almost seductively so. A steady climate and lush forests kept us nestled in the branches for millennia longer than the Chelok, nurturing us into stronger climbers and gatherers but leaving us slower to develop the intricate hand movements required for shaping stone, carving wood, or smelting metal. It’s hard not to wonder whether, had our ancestors been forced from the trees earlier, we might have led instead. Yet there is a deeper lesson in the Chelok’s success. Their lack of over-specialization in any one direction left them adaptable, a crucial trait that allowed them to master tools early and turn necessity into a source of power.

There seems to be a pattern here which I am certainly not the first one to point out, nor will be the last one to point it out, but that may explain, at least in part, why the Dominion has developed so late in comparison to them. Forget not, that despite their fragile fragmented state nowadays, the chelok peoples once ruled far and expansive swathes of space still uncharted by us to this day.

In a way, our more stable climate kept us in the trees longer, providing little incentive to move forward technologically. Our stronger, more specialized grip was suited to our environment, but it also delayed our need to develop tools suited for open ground. The Chelok, by contrast, had to adapt quickly to survive on the plains, and this drive toward tool-making allowed them to leap ahead. Despite our similarities, it seems that evolution's hand—working through environmental pressures—has favored them in ways that we never considered. Perhaps, if our circumstances had been different, with a less stable environment pushing us out of the trees earlier, we might have been the ones leading the way in technology.

[missing image]

Another key distinction between the Hoku and the Chelok lies in the shape of their skulls. Chelok have remarkably short, almost round or oval skulls, with most of the cranial space occupied by their relatively large brains. Their faces are notably flat, featuring two forward-facing eyes placed near the center, one on each side, with white sclera and individually unique iris colors. In the center of their face sits a prominent, tetrahedral nose with varying degrees of roundness, and directly beneath it, a mouth that, when closed, remains within the width of the eyes. Unlike some species with fangs or sharp teeth, the Chelok have flat, blade-like teeth at the front for cutting food and broad molars in the back for grinding, adapted for prolonged chewing. Their short, muscular tongues and vocal cords are well-suited for complex vocalizations, which, as with us, serve as their primary mode of communication.

With one rounded ear on either side of their head, the Chelok auditory structure is streamlined solely to funnel sound inward, lacking the expressive range of movements we have in our ears. However, their faces are capable of a vast array of expressions—far more diverse than ours. It was both amusing and intriguing for me and my crew to witness their seemingly endless range of facial movements. Unlike the Hoku or other species with protective coverings like feathers, scales, or thick hides, the Chelok are covered in a thin layer of hair over smooth skin that varies in shade much like our own. Their hair grows most prominently on the head, face, chest, and in their private areas, leaving their skin otherwise exposed. This trait not only contributes to their distinctive appearance but also serves as a canvas for their endless cultural expressions—tattoos, piercings, ceremonial paintings and more.

THE CHELOK FROM URAFAR

The majority of Urafar's population has skin tones close to ours, ranging from dark to occasionally lighter or even darker shades. Many Chelok men opt for shaved heads, a practical look that contrasts with the intricate braids worn by those in higher ranks, which are often adorned with decorative beads and wraps. Chelok women, however, are a more complex and fascinating sight. In about a third of the population, cultural or religious traditions require women to cover their faces and bodies, a practice not followed by the rest, where no such restrictions apply. Observing this variation offered us some insight into gender distinctions within Chelok society.

One notable difference is that Chelok are mammals, as evidenced by their females' ability to nourish their young from one of two mammary glands on the chest—similar to some burrowing animals native to Hokushoku. Interestingly, unlike the men, all Chelok women appear to have complete freedom over their head hair. Many women in prominent roles tend to keep their hair tied short or shaved entirely, though the cultural significance of this practice remains unclear to us. As we continue learning about their customs, it's apparent that even seemingly mundane aspects like hairstyle hold layers of meaning and societal symbolism in Chelok culture. Contrast that to the natural arrangement of feathers hoku share with their family members and lineage, often set to a proud maximum standard with little stylization, or shaven down entirely as some cultures still do.

[missing image]

Apart from the peculiarities of their customs, we were also taken aback by the linguistic diversity present everywhere. While signs are standardized to just four writing systems, it was common to see store banners showcasing at least ten different scripts. Merchants would eagerly switch between languages to try and make a sale, often growing frustrated when we couldn't keep up. It didn’t take long for us to pick up that the side-to-side head swing, which for us means “no,” is also used by the Chelok to convey the same meaning.

Their skin, much more delicate than ours, combined with their lack of natural defenses other than physical strength, makes clothing an essential part of Chelok life. Not only does it serve as protection from the sun, but it plays a critical role in daily activities, rituals, and status displays. The Chelok have a particular fondness for incorporating metals, glass, and jewels into their garments and accessories, which blend tradition with modern fashion in fascinating ways. It’s hard to determine what’s purely traditional versus what’s fashionable at the moment, as both seem to coexist seamlessly. During a trip to the markets, we found an array of both natural and synthetic textiles. Some clothing featured sharp, straight cuts and muted color palettes, while others were adorned with floral or vibrant, nature-inspired patterns. Ironically, our attempts to blend in with their style only made us stand out more. I, for one, opted to stick with my robes a little longer—they were far more familiar to me.

A day on Dhegōm is only three-quarters as long as our standard day, so we quickly found ourselves needing to return indoors as the hours flew by. This, of course, led us to purchase some questionable quality wristwatches, a necessary but somewhat comical addition to our gear. The first few days were filled with discoveries, but our mission had yet to truly begin. Our translator was busy attempting to contact the local archaeological society, so, for now, we focused on soaking in the vistas around the sprawling city of Urafar.

[missing image]

One thing that became strikingly apparent after a few hours of touring the city— or, perhaps more accurately, what was not apparent— was the complete absence of synths. At best, we saw Chelok individuals sporting various bodily extensions— jaws, arms, spinal modifications, and even retinal enhancements— none of which were hidden. In fact, some Chelok proudly wore torn clothing to accentuate these modifications, whether arms or legs. This openness towards body augmentation seemed commonplace, yet the complete lack of synthetic beings was puzzling to say the least.

You see, across much of the Dominion, as it was in the Expanse, the presence of "synths"—beings fabricated en masse or on-demand to fulfill specific roles in the workforce—is commonplace. These synthetic beings are often employed where colonists are scarce, acting as workers, servants, and even soldiers. The Chelok, however, refer to them as Specters, perhaps a nod to the unsettling aura that these autonomous constructs carry. The presence of such constructs, especially those with independent bodies rather than being anchored to ships or buildings, is a source of discomfort for many Chelok. This aversion is rooted in what is known as the Spark Veto, a deeply ingrained cultural trait shared by much of Chelok society. The Spark Veto is essentially a rejection of artificial intelligence, limiting even the rudimentary constructs within Chelok territories. Some Chelok factions go so far as to reject all technology beyond basic tools, even refusing to use iron or steel, as an extreme manifestation of this belief.

This reluctance to embrace fully autonomous constructs is likely tied to the fall of their ancient empire—or perhaps even its foundation—shaping their collective psyche in ways that lead to a deep-rooted fear of what they perceive as unnatural. In contrast, however, the more prominent and developed Chelok societies seem to hold a contradictory belief: a desire for the post-human, not necessarily as a deliberate act, but perhaps as a deliberate or even subconscious perversion of the natural order. These Chelok believe that technology should serve to elevate the organic, not replace it, and that the boundaries between organic life and machine should remain carefully maintained. This tension between reverence for the natural world and the allure of technological transcendence is a defining feature of their culture, leaving a curious imprint on their society.

At first glance, it might appear that the Hoku are far more civilized than the Chelok—more orderly, more advanced, more secure in our technological mastery. However, this apparent sophistication is, in part, the result of the extinction of the more “uncivilized” branches of our peoples. The Hoku who once lived in the chaotic throes of progress and destruction, those who failed to adapt to the new world order, have long been stifled out of existence, leaving only a remnant of what they once were—a hollow imitation of our former selves, struggling to reconcile our past with the present. The remnants of those pre-cataclysmic Hoku ideals still linger, but they no longer define us as a whole.

For those unfamiliar with our heritage, let it be known that the Hoku across the Dominion today represent three distinct genetic trunks, a direct consequence of the devastation that once threatened our species with extinction, and the unity forged in the aftermath of that crisis.

Approximately four thousand years ago, the Hoku were confined to their homeworld, having recently discovered the atom’s power but finding that such advancement only escalated tensions rather than calming them. Rapid scientific progress left us with little time to absorb or temper our newfound capabilities, and anxieties flared, ultimately culminating in the horrors of nuclear war. When the dust of that catastrophic conflict finally settled, the few survivors saw only one path forward: they needed to engineer a subset of our kind that could endure the radioactive wastelands of our ravaged planet and could carry on their legacy with a resilience surpassing their own. Thus, the Kahikopafi—or "divine servants"—were bred, a people designed to be hardier and more obedient. Although there were inevitable tensions, the Kahikopafi gradually replaced a significant portion of the original Hoku population, excelling in countless societal roles due to their unique abilities and genetic adaptations.

The original Hoku regarded the Kahikopafi as extensions of themselves, a symbiotic lineage, and the Kahikopafi embraced this vision, viewing the creation of sentient synths as the next logical evolution of the Hoku legacy. By the time Hoku settlers and their Kahikopafi counterparts reached the Expanse, our synthetic beings—our "sentient machines"—had already done much of the preparatory work, laying the groundwork for our civilization and laboring without reward but the privilege of coexisting among us.

In contrast to us, the Chelok have retained much of their original essence, perhaps because they never underwent a similar cataclysmic shift in their own evolution. Dominion researchers, in fact, have mapped the Chelok genome across space and time with a surprising degree of success, hoping to answer a lingering question that still evades us: where did the Chelok come from? Despite years of investigation, their origins remain elusive, as they do not appear to be native to any known system within a thousand light-years from Argost. Unlike the Hoku, who have lost and rebuilt much of our identity over the millennia, the Chelok remain remarkably close to their original genetic makeup, maintaining a cultural and biological continuity that we can only attempt to understand from the outside.

Still, despite their biological continuity, the natural drift of isolated populations and environmental pressures have led to many streams of Chelok losing the ability to interact with the advanced technology of their forebears. Whether by accident or design, the bloodlines capable of activating their genetic locks have been bred out of certain populations. In some regions, this has rendered entire peoples unable to access the rich heritage of their ancestors—perhaps for the better, as the loss of this knowledge has kept them from repeating the mistakes of the past.

[missing image]

Another peculiar detail that stood out across the city was the unusual absence of the color blue. While we were unable to translate the precise term for the color, it became evident that blue pigments—whether light or dark—were nearly non-existent in the city's vibrant artwork. Instead, the streets and buildings were awash in rich ochres, reds, and oranges, with black and white playing prominent roles in their designs. Which is an interesting indicator of what ancient lineage these chelok descend from, as they are biologically less sensitive to any blues—as a result of that, dark blues and black are used interchangeably all over the place. At this point it is a commonly known trait of them, which might link them to a very ancient splitting event and later re-merging of those among them who can better perceive blue-green and those who cannot.

During our introduction to the city, we had the opportunity to sample local foods and specialties unique to the Dominion. The canyon’s varying temperature and pressure zones have created a diverse agricultural landscape, with different plants and animals cultivated in distinct regions, offering a variety we’ve never encountered elsewhere. We observed characteristic animals, bred exclusively by the Chelok, that we’ve only seen in historical and archaeological records, but never in the flesh. I was particularly struck by the wide range of colors among what they call "chickens." Typically, such variety would indicate different breeds, but these chickens were purposefully bred over millennia to showcase this diversity.

They also have mounts, some of which are considered delicacies by certain cultures. In that regard, I’d compare their called horses to our antillos—smaller, hairier, with no horns or large digging claws. Much alike them these animals can't be found anywhere else the chelok haven't set foot yet, probably imported from their homeplanet or somewhere else close to home, wherever that may be. For our first meal, however, we opted to stay closer to home, ordering a mix of insects and crustaceans. The cook put on quite a show, tossing and stirring our food with impressive speed and height between pans before serving us a steaming hot dish, accompanied by a large glass of cold, sweet juice from a green fruit he opened right in front of us. Once the food had cooled enough to savor, we found that Chelok cuisine lives up to its reputation—possibly even surpassing the trader texts, depending on the dish.

After a local week had passed, we finally received an invitation from the Urafar Archaeological Society to visit a location known as Northern Site D-24. To our surprise, we were greeted by a short, pale elderly Chelok who was dressed almost exactly like us, though our team had come prepared in typical Chelok hiking gear. This sight brought some amusement, as the only one dressed like a fellow Hoku was, unexpectedly, our host. Even more surprising, he spoke flawless Hukat, which immediately set him apart from the locals we had encountered. It turns out the UAS had assigned us a Hoku xenoarchaeologist. I'm not entirely sure if I should feel slighted by this decision, given the subtle implication that our knowledge of their sites is limited, or grateful for the insight he might bring. Professionally speaking, I suppose gratitude is the more reasonable response, considering the UAS knows how much of our records were lost during The Fall of Hokushoku.

After a pleasant lunch at the Society's sleek, minimalist building, we set out in rovers toward the site, located about 50 kilometers upstream.

- M.O. Valent, originally posted on 14/03/2023

last revised on 14/11/2024

Happy π-day